Replacing googletest with jctest

*You can find the code at the github repo or go to the documentation page* Or skip directly to the results

Overview

Every now and then, I feel the urge to find out where the time building a project is spent. I may not always be able to do something right away, but I usually learn something new about the codebase.

This urge is often prompted by some new tool mentioned to me or posted on twitter. In this case, Aras Pranckevičius made some contributions to clang that allows you to check out the time spent in the various parts of your code, when compiling.

First, I instrumented the buildsystem (we use waf) to output the build times for each indiviual .cpp file. One thing that immediately stood out was that the test_*.cpp files were at the top of the list.

So I picked one of the first tests I saw in the list, that had a high time versus lines of code ratio. This is the entire test_align.cpp:

|

|

It consists of 2 test cases, and 3 asserts in total.

This is a very small test.

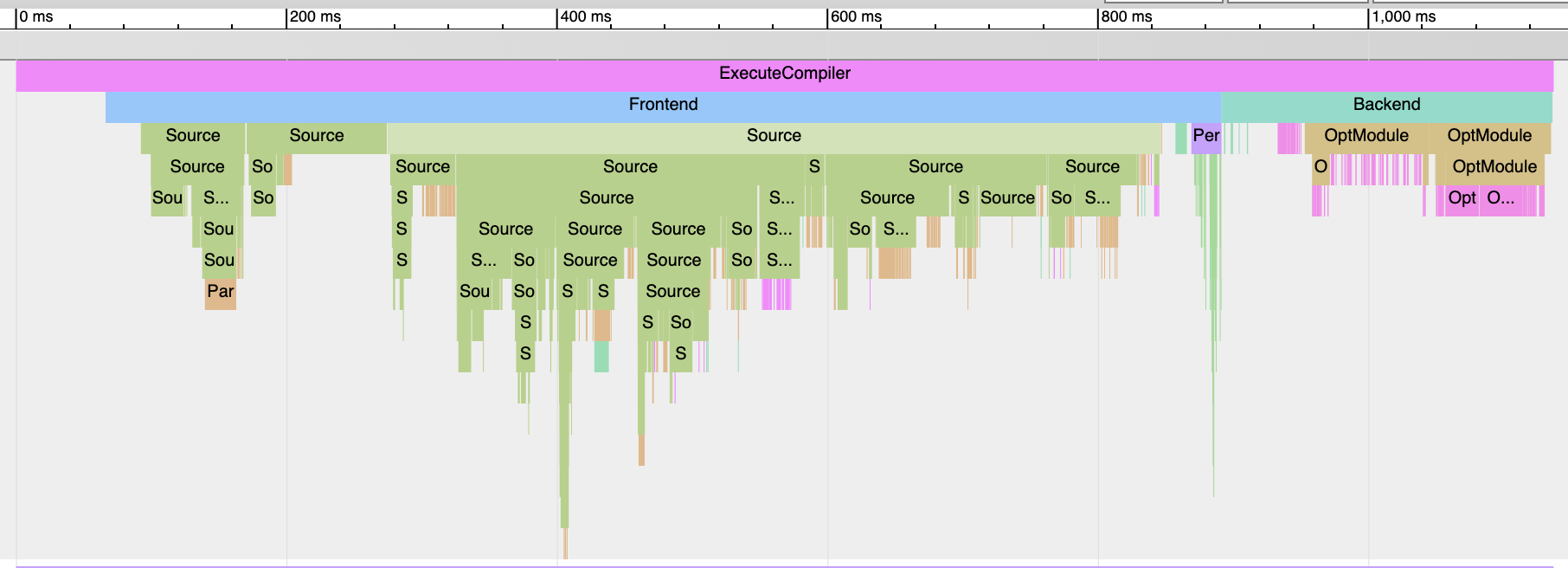

And this is what the clang trace looked like:

One can see that reading gtest.h takes up a huge chunk of the time here, about 570ms.

Of course, in practice it compiled in ~0.68 seconds, but that’s also quite a high number for such a small test.

C++ Templates

Most of us use a computer from this millenia, and they’re pretty powerful. Even the laptops. And ~0.68 seconds is actually a quite lot. So I started to wonder what the cause was for this? googletest works as a precompiled library, so it isn’t compiling all that test code. But that means the headers are quite heavy.

In our build setup, we have one test .cpp file for each test, so we’ll pay that cost for each test.

By quickly glancing over the code, you will quickly notice that gtest.h consists of ~2500loc, and it includes 10 other internal includes, totalling above 10000loc. And that’s just for the includes (it has a lot of .cpp files compiled in that library too).

And my guess was that the C++ templates was the main cause for the long compile time.

First stab

Surely one doesn’t need 10+k lines of code to write the tests we need? I wouldn’t have to reimplement everything, just what we needed.

I had written some tiny C test framework earlier so I had a little bit of a head start there. It later slowed me down and cluttered the code, since I attempted to support both C and C++ in the same framework

Adding support for the basic cases, TEST() and TEST_F(), took about maybe two evenings.

They represented about 85% our our test cases. The rest were using TYPED_TEST() and TEST_P().

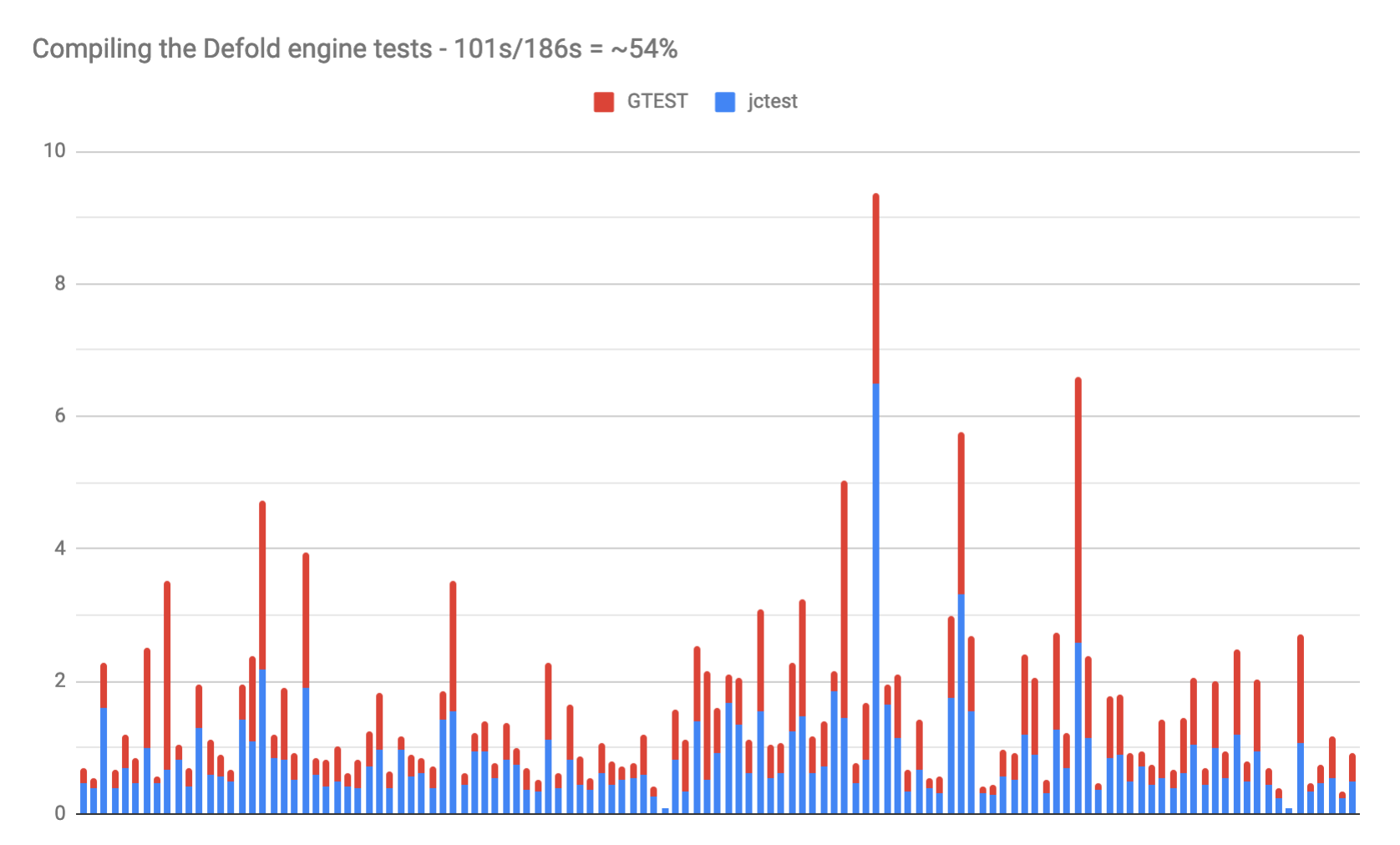

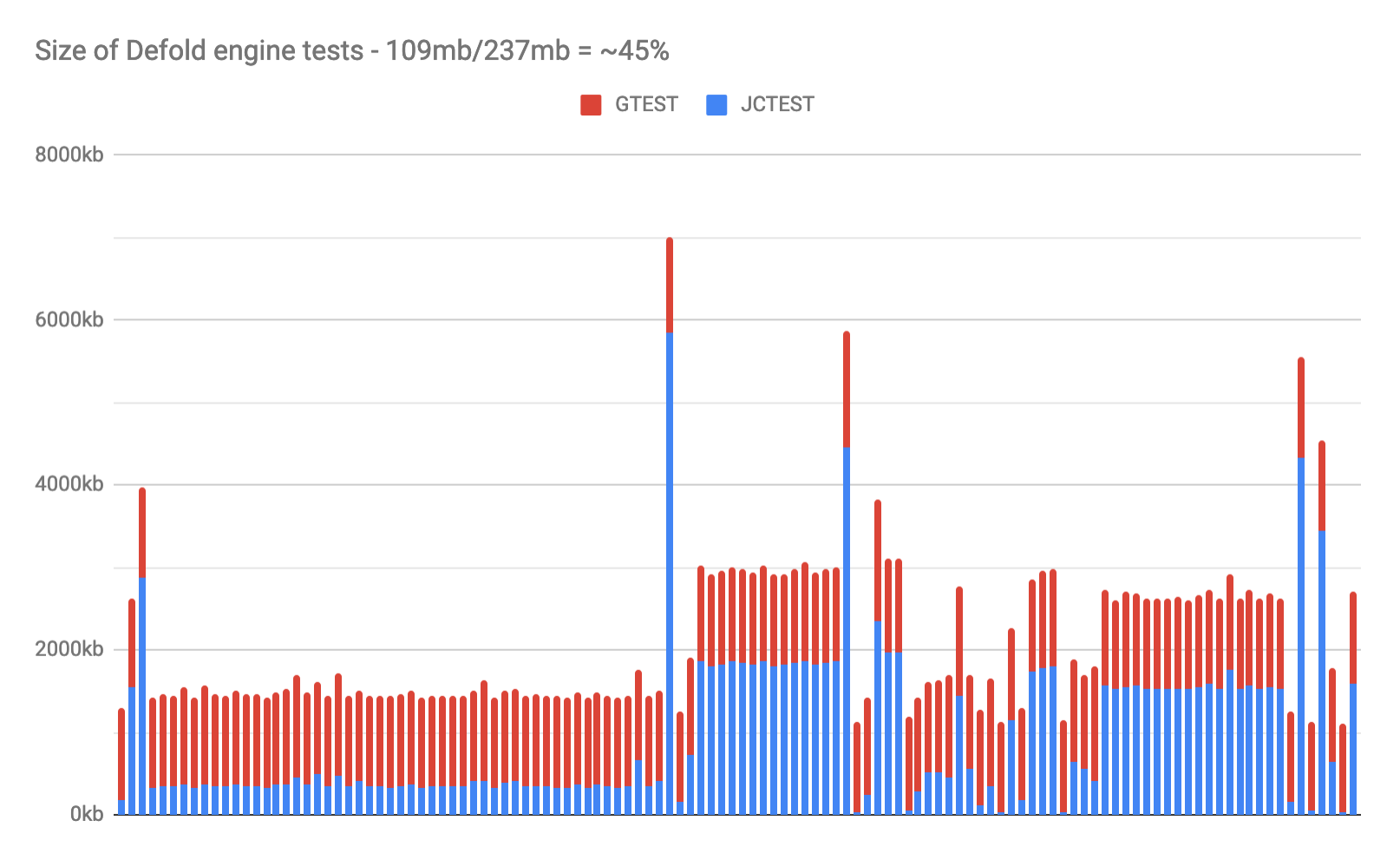

The results were really promising, showing a good save in both compile time and also build sizes.

Comitting to it

At this point, I was hooked. It totally felt doable, so I decided to go all in and implement the outstanding features needed to become a replacement for the old library. And those features were definitely going to need c++ templates.

So I set up some design rules…

Our use case

This entire endeavour was started to help out our code. I simply wanted the features we needed, and I opted out of trying to have 100% parity in actual behavior, as long as our code gets tested as expected.

It works for us, simple as that.

No STL

A known culprit for compile times and code bloat is stl and std::ostream in particular is a culprit.

Also, STL implementations is often enough a source of ABI troubles. basic_string in the link errors anyone?

So I simply opted out of it. We used the feature in one test, but we didn’t really need it.

Modern C++ C++98

We use a C-like-C++ approach, with very few templates. We don’t have any great need for C++11 features.

We are not using C++11 in our compiler step, but rather rely on the default flags of our compilers.

This means we use C++98 for some platforms. And I think many projects out there uses that too?

And, since we don’t need it, I opted for supporting C++98

This meant opting out of variadic templates, for instance, which could have been useful (perhaps). But instead the code became a bit more readable. perhaps a bit subjective, I know

Single file, header only library

As I wanted to make the framework easy to use, I opted for the single file header only approach, as popularized by Sean Barret and his slew of stb libraries.

The biggest reason for this was that, if successful, I didn’t have to maintain a C++ library for 7 different platforms/architectures.

1000 lines of code

In my initial effort, the framework was around 600 loc. And even though the needed feature set is more important than the number of lines, I believe that it also is a metric of readability.

Of course, the first stab was the easy part, layout out most of the code structure, and implementing the easier things. Fixing the rest of the features would perhaps double the amount of code. But, I thought 1000 lines is a good number to aim for, so that’s what I did.

This meant that I cut some features along the way that wasn’t necessary, like even fancier log output. It also helped me focus on the end goal better.

The unholy alliance

To support the features that we needed (parametric typed tests, good typed error output) it turns out it becomes a lot trickier.

The test framework is using the preprocessing a lot, and it’s using a bunch of #define's to produce the structure of the framework.

It also uses templates to implement the particulars. And in combination, these two became extremely cumbersome to read and understand when things went wrong. This is where the compile flag -E (for gcc/clang) comes in handy, for producing the actual code output, so one can debug the code generation.

I cannot honestly say the internal parts of the framework is easy to read, and I apologize in advance for that.

Assert on death

The googletest implementation checks for different support to catch errors in the code (e.g. forking).

This was a bit over the top for our use case. We simply needed to know that the code asserts in certain cases. And the implementation was based on signal handlers and setjmp/longjmp, which made it short and

readable.

Results

I think the results were very much a success. We shaved off ~85 seconds cpu time on a local build (OSX).

That’s a ~46% save! And the build sizes shrank with ~55%!

These graphs show the before/after in each column

On our CI machines, with multicore support, this framework saved us ~20-30 seconds out of ~300s on Linux/OSX, and ~3min out of ~11min on our Windows builds. Yeah, checking the Windows compile times is high on the list

Wrap up

Check your timings

“Is it reasonable to take that much time?"

This is true for the build system as well as your runtime. Think of the time it saves you, your colleagues, your company, your customers etc.

E.g. I should have identified this as a performance issue a couple of years ago… doh!

Check your code size

“Is it reasonable to take that much space on disc?"

Remove code you don’t need if possible.

Code size is not something that you take lightly either. It will affect the product as well in either turnaround times, CI costs, download size etc.

In our case the build system actually ran ~6s faster since the tests were smaller.

Difficulty

As a whole, I would classify this endeavor at an intermediate difficulty. I would have found it a lot easier if I were better at C++ templates. I rarely use them. And it’s noteworthy that it didn’t require any “modern c++” to do this.

Also, a lot of time were spent on reading the googletest code, to figure out, best I could, how the the code was structured.

For the whole implementation, I estimate to have spent ~2 man weeks on this project.

Reinventing the wheel?

Someone might call out something about "premature optimization" or "reinventing the wheel" (as you hear from time to time). Here´s a great post by Joshua Barczak on the subject.

It’s not about “reinventing” something, but improving on it. If noone tried to improve on the wheel, we’d still be stuck with some old wooden wheel.

I’m also an advocate for implementing things yourself. One reason is to learn about the subject, so you can make informed decisions. Another reason is that you can customize code to your project, removing things you don’t need or improving on those you have (e.g. replacing the stl containers with smaller and faster versions)

Why pay for something you don’t need or want, if you don’t have to? Even if you are ok with the current solution, are your colleagues? Or your boss?